America Divided: What the Election of 1860 Can Teach Us

Polarization isn’t new. The lessons of 1860 remind us why division matters, and why our present moment is unique.

Much of our dialogue today is dictated by the idea of political division. Indeed, Americans are more polarized than they have been in years, with very little room for agreement, with most Americans saying that the two parties cannot even agree on basic facts (Shearer 2025). It is in this environment that many Americans look to the past to understand not only how we might react to our present predicaments, but also how to look for a precedent. While there have been many points in our history where division has spawned, the election of 1860 is perhaps one of the most significant in its intensity and the violence that came with it.

The Haunting Specter of Slavery

One of the biggest issues that permeated the American body politic, leading up to the election and in prior elections, was the issue of slavery. By 1850, an estimated 3.2 million people were enslaved in the South (Roland 2002, 2). During that time, most Northern states had abolished slavery, though not all. Southern states, meanwhile, pressed for their expansion and demanded federal protection of what they considered their property rights.

These debates went so far as to argue before the Senate that slavery was beyond the power of Congress publicly. Figures such as John C. Calhoun, then a Senator, warned in 1837 about the threat of abolition and objected to the Senate's continued focus on addressing petitions from abolitionists, which he referred to as "these insulting petitions." He argued that such concerns were unacceptable and that slavery was "beyond the jurisdiction of Congress—they have no right to touch it in any way, shape, or form, or to make it the subject of deliberation or discussion." (Calhoun 1837, 55-56). To Calhoun, slavery was a right beyond the power of the government.

Other prominent Southerners went further, arguing that the abolition of slavery was detrimental to the well-being of African Americans, who they deemed intellectually inferior. In an essay, Thomas R. R. Cobb, who would later be one of the major architects of the Confederate Constitution, asserted that: "Notwithstanding the very labored efforts made for their intellectual improvement, taken as a body they have made no advancement" (Cobb 1858, 78). It will not surprise anyone, but it is worth noting that slavery and white supremacy were heavily intertwined. One served to justify the other.

To many in the South, slavery did not simply need protection; it had to expand. Their legislative record shows that, at the very least, pro-slavery Southerners were perfectly willing to expand their influence into Northern states and see their ownership of enslaved people recognized as legitimate.

With the passing of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Northerners saw their states subject to slave hunters, and any person who tried to help escaping enslaved people could face 6 months in jail and a $1,000 fine (National Constitution Center 1850). Combine that with the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which created Kansas and Nebraska and allowed for people to decide if their state would be a free or slave state, and violence began to erupt among pro-slavery and anti-slavery advocates.

This violence would spill over in 1859, when John Brown and a group of abolitionists attempted to seize the federal arsenal in Harper's Ferry in the hopes of inspiring a slave revolt (Noyalas 2020). Though Brown failed in his endeavor and was executed for treason, his revolt terrified southerners who feared enslaved people turning against them. To them, Brown's raid was not only a sign of the danger of a slave revolt, but a sign that slavery had to be upheld against outside, northern influence.

This fear would be central in the coming election.

The Battle of Ballots

By 1860, the issue of slavery was tearing apart the nation. The Whig Party, the main source of opposition to the Democrats before the Republicans, had fallen apart over the issue. Eventually, Northern Whigs organized to form the Republican Party in 1854 (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2025). This young party would be at the center of anti-slavery thought.

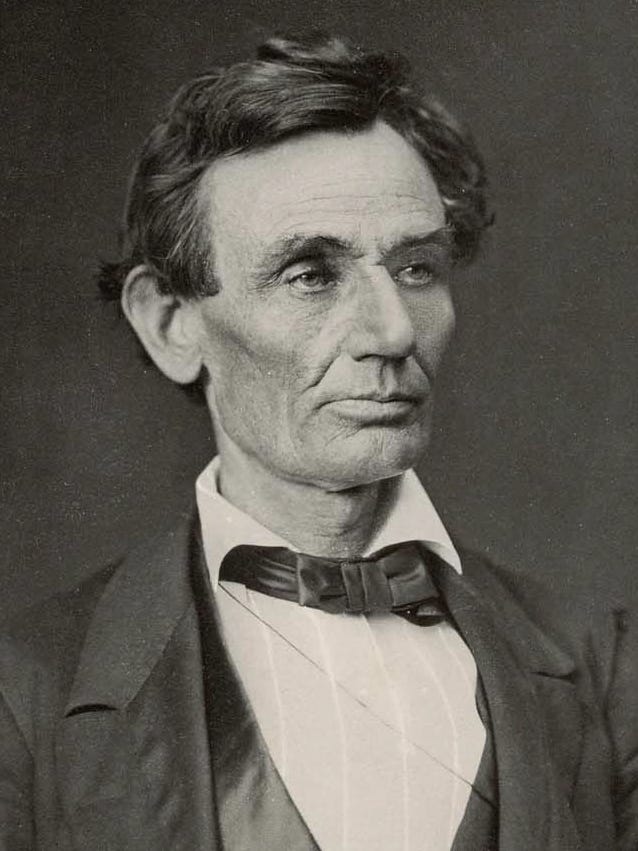

While it may seem inevitable now for people to point to Lincoln as the Republican choice, that was not the case when the Republicans first started choosing candidates. Lincoln had previously lost a Senate race and lacked the name recognition of other prominent figures. Figures such as William Seward of New York had an advantage over the Illinois lawyer. He was a former governor, a sitting U.S. Senator, and a fierce anti-slavery advocate (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2025). His only problem was that he had been criticized for comments he made, arguing that there was a higher power than the Constitution. He further asserted that there was an irreconcilable conflict between slavery and freedom (Donald 1995, 236). This firmness made it easier to brand him as an extremist, and his reputation suffered because of it.

Lincoln, by contrast, was a moderate on slavery. He had maintained a balancing act when talking about the founders and slavery, arguing that there were political realities that meant slavery could be tolerated in areas where it existed, while also opposing its expansion into any new territories (Danoff 2015, 50).

Lincoln had publicly stated that slavery would inevitably expand at the expense of the free society of laborers; this was not an abolitionist critique per se, it was more in the vein of an anti-slavery argument as well as an acknowledgement of the political realities of his day (Donald 1995, 234). Unlike Seward, however, Lincoln had not presupposed conflict or suggested there was a higher power than the Constitution. He would benefit significantly from his restraint in the election.

On the Democratic side, the fight was even more intense, with the convention in April being unable to decide how it wanted to address the issue of slavery. Southern Democrats wanted slavery to be protected everywhere through a federal slave code and demanded that the party adopt the position (Burlingame, 2016).

However, Northern Democrats supporting Stephen Arnold Douglas, who had previously defeated Lincoln for the Senate, refused to accept the position, and the party was forced to adjourn and reconvene in June. After some maneuvering, Douglas became the nominee. Pro-Slavery Democrats, however, walked out and formed their own party around the incumbent Vice-President and pro-savery advocate, John C. Breckinridge (Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d).

The result was a split ticket.

When Lincoln was nominated for the Republican ticket, allies in Seward's camp were reportedly surprised by the level of influence that he had ascertained, but Lincoln's maneuvering had paid off (New York Times 1860a). By the end of the election, Lincoln triumphed in the four-way race, securing 1,866,452 votes to the Democrats' 1,376,957, under 40 percent of the vote. The pro-slavery Southern Democrats took 839,781, and the Constitutional Unionists took 588,879 (Donald 1995, 256). Despite not winning the popular vote, Lincoln was on his way to the White House.

It would prove more challenging than he anticipated. By November 10th, South Carolina's legislature unanimously elected a convention to consider the issue of secession, and within a month, all of the states in the lower South were beginning to consider secession (Donald 1995, 257). Lincoln’s election confirmed the worst fears of Southerners, who were convinced that the North was coming after slavery, and they chose secession to avoid that end, which provoked a war that killed over half a million Americans.

Concluding Thoughts

This is this publication's first serious article, which is part of the reason it is so long. When it comes to the validity of Civil War comparisons, people need to remember that every historical event has its context and causes.

While yes, there are similar points of tension in terms of intensity, it is a mistake to treat the division our country faces as synonymous with the 1850s or the 1860s. As historian Kevin Levin rightly pointed out in his own piece on the subject, America is "simply not divided along sectional or regional lines" (Levin 2025). America faces an issue of political identity, human rights, and an increasingly dangerous media environment, but we are not abolishing slavery or dealing with the sectionalism of the 1850s and 60s. Our circumstances are unique in their own right. We should treat them that way.

References

American Battlefield Trust. n.d. “States’ Rights.” Last updated December 18, 2008; September 27, 2023. Accessed September 16, 2025. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/states-rights?utm_source.

Baum, Dale. 1984. The Civil War Party System: The Case of Massachusetts, 1848–1876. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. With Internet Archive. http://archive.org/details/civilwarpartysys0000baum.

Benedict, Michael Les. 1980. A Compromise of Principle: Congressional Republicans and Reconstruction, 1863–1869. New York: W.W. Norton.

Burlingame, Michael. 2016. “Abraham Lincoln: Campaigns and Elections.” Miller Center, University of Virginia. October 4, 2016. https://millercenter.org/president/lincoln/campaigns-and-elections.

Calhoun, John C. 1837. “Speech in the U.S. Senate, 1837.” In Defending Slavery: Proslavery Thought in the Old South, edited by Paul Finkelman, 55–59. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2003.

Civil War Causes. n.d. “Chronology of the Secession Crisis.” Accessed September 15, 2025. https://www.civilwarcauses.org/secesh.htm.

Cobb, Thomas R. R. 1858. “An Inquiry into the Effects of Abolition in the United States, 1858.” In Defending Slavery: Proslavery Thought in the Old South, edited by Paul Finkelman, 77–83. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2003.

Danoff, Brian. 2015. “Lincoln and the ‘Necessity’ of Tolerating Slavery before the Civil War.” The Review of Politics 77 (1): 47–71.

Donald, David. 1995. Lincoln. New York: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1998. “John C. Breckinridge.” July 20, 1998. https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-C-Breckinridge.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2025. “William H. Seward | US Secretary of State, Civil War Diplomat.” https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-H-Seward.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. n.d. “Salmon P. Chase | 19th Century US Politician, Chief Justice of Supreme Court.” Accessed September 15, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Salmon-P-Chase.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. n.d. “Whig Party | History, Beliefs, Significance, & Facts.” Accessed September 16, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Whig-Party.

Finkelman, Paul, ed. 2003. Defending Slavery: Proslavery Thought in the Old South. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Levin, Kevin M. 2025. “We Are Not Living Through the 1850s or Headed Toward Another Civil War.” Civil War Memory (Substack newsletter). September 13, 2025. https://kevinmlevin.substack.com/p/we-are-not-living-through-the-1850s.

McCurry, Stephanie. 2010. Confederate Reckoning: Power and Politics in the Civil War South. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

National Archives. 2021. “Kansas–Nebraska Act (1854).” July 12, 2021. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/kansas-nebraska-act.

National Constitution Center. 1850. “The Fugitive Slave Act (1850).” ConstitutionCenter.org. https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/historic-document-library/detail/the-fugitive-slave-act-1850.

Noyalas, Jonathan A. 2020. “Harpers Ferry during the Civil War.” Encyclopedia Virginia. December 7, 2020. Last updated February 18, 2025. Accessed September 16, 2025. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/harpers-ferry-during-the-civil-war/.

Roland, Charles P., 2002. An American Iliad: The Story of the Civil War. 2nd ed. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

Schulten, Susan. 2010. “How (and Where) Lincoln Won.” New York Times Opinionator Blog. November 10, 2010. https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/11/10/how-and-where-lincoln-won/.

Shearer, Elisa. 2025. “Most Americans Say Republican and Democratic Voters Cannot Agree on Basic Facts.” Pew Research Center. July 30, 2025. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/07/30/most-americans-say-republican-and-democratic-voters-cannot-agree-on-basic-facts/.

Stevens, Frank E. 1923. “Life of Stephen Arnold Douglas.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908–1984) 16 (3/4): 274–673.

Taylor, Lenette Sengel. 1985. “Polemics and Partisanship: The Arkansas Press in the 1860 Election.” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 44 (4): 314–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/40027736.

The American Presidency Project. 1860. “Republican Party Platform of 1860.” May 17, 1860. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/republican-party-platform-1860.

The New York Times. 1860a. “Republican Ticket for 1860: Abram Lincoln Nominated.” May 19, 1860. https://www.nytimes.com/1860/05/19/archives/the-republican-ticket-for-1860-abram-lincoln-of-illinois-nominated.html.

The New York Times. 1860b. “What’s to Happen.” October 11, 1860. https://graphics8.nytimes.com/packages/pdf/opinion/timeline/lincoln-1860.pdf.

“Republican Party National Platform, 1860.” n.d. Accessed September 12, 2025. http://cprr.org/Museum/Ephemera/Republican_Platform_1860.html.